In his new biography of SNL legend Phil Hartman out today, “You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman,” Chicago Sun-Times newspaper reporter Mike Thomas captures the man who represented “the glue” of Saturday Night Live during what many consider its greatest cast era of the late 1980s.

In his new biography of SNL legend Phil Hartman out today, “You Might Remember Me: The Life and Times of Phil Hartman,” Chicago Sun-Times newspaper reporter Mike Thomas captures the man who represented “the glue” of Saturday Night Live during what many consider its greatest cast era of the late 1980s.

That’s when Thomas first started watching SNL himself. And he, much like most viewers of SNL, cites the era he grew up with the show as the pinnacle.

“Nobody had really written about Phil’s life,” Thomas told The Comic’s Comic. “I knew a lot about Phil’s work, and I knew a lot about Phil’s death, but I didn’t really know about everything in between.”

Researching and reporting that in between, Thomas said he “grew to love him even more.”

“Every human has his flaws,” Thomas said. “But Phil lived such a colorful life. He was deeply curious about all kinds of things, whether it be flying, or boating, or religion, or philosophy.” Or designing album covers. And of course, becoming a vocal and visual chameleon who elevated his scene partners, first onstage with The Groundlings and Pee-wee’s Playhouse, and then onscreen via SNL, NewsRadio and The Simpsons.

Grantland recently polled its readers for the greatest SNL cast member ever from the show’s first 39 seasons, and Hartman finished runner-up to Will Ferrell.

“I’m biased,” Thomas said of Hartman. “He’s my top cast member of all-time. I can’t imagine that he’s not in the top 3 or top 5 of most fans. He was underappreciated because he would take these smaller roles. That worked against him.” He certainly wasn’t as loud or outsized as Ferrell or Adam Sandler, Thomas said.

What place does Hartman ultimately hold in SNL lore?

“Phil wanted to be Dan Aykroyd going in, being this indispensable guy, and I think he succeeded and more,” Thomas said. “I think Larraine Newman told Lorne (Michaels) early on, ‘He’s Danny without the drama.'”

Hartman would have turned 66 tomorrow. He died in 1998, shot and killed by his third wife, who then turned the gun on herself. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just this past summer.

In this exclusive book excerpt provided to The Comic’s Comic, we catch up with Hartman in 1985, when the 37-year-old actor was disillusioned with the progress of his acting career. Hartman was a member of The Groundlings troupe in Los Angeles, writer and background player for his Groundlings mate Paul Reubens and his breakout character Pee-wee Herman, and passed over for Saturday Night Live by another member of the Groundlings, Jon Lovitz.

“Amid Phil’s mounting frustration about his seemingly stagnant career, and in the way that only mothers with blind confidence in their progeny can do, Doris Hartmann encouraged her middle child to keep his chin up—everything would work out for the best. She told him other, less heartening things, too. A psychic Phil’s sister Martha had visited confirmed it, predicting that Phil would be “very successful.” Doris underlined “very.” She told him other, less heartening things too, namely that life’s clock was ticking and Rupert was “depressed” he didn’t know his kids better. Doris, though, knew that neither he nor she could turn back time — that it was “too late to make amends for all the things we should have said and didn’t — all the things we said and shouldn’t have.”

As Doris advised, Phil forged onward. He spoke with a casting boss at ABC, who told him (as Lisa had years earlier) that a return to acting school might be just the thing to help him transcend mere characterizations and find the funny in Phil Hartman. Tony Danza and Ted Danson were playing versions of themselves with great success on Who’s the Boss and Cheers, respectively, and Phil would do well to follow their leads. But he wasn’t buying it. Even before Katz had tried to coax him out at the Groundlings, being himself — or even a close facsimile thereof — had never been Phil’s forte. As he told the L.A. Times in 1993, “I wasn’t that secure with myself. I felt vulnerable trying to be anything close to myself on stage or in front of a camera. I felt more comfortable being buried in a person. The deeper the burial, the better.” Meanwhile, he watched friends and former colleagues become famous.

Reubens, for one, was already nationally known and about to break big thanks to his tour and multiple appearances on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. Lovitz, too, was on the rise. In a development that surprised some, Phil’s Groundlings mate and recent voice co-star in the Disney animated film The Brave Little Toaster was selected to join Saturday Night Live during its 1985–86 season. If there was jealousy on Phil’s part, Julia Sweeney failed to sense it. More than a few people, though, were puzzled by Lorne Michaels’s decision to hire Lovitz over Phil. “I remember one of the times Lorne was at the Groundlings, standing in the back watching a show, and I was standing next to him,” Tracy Newman says. “And I said, ‘Are you here for Phil?’ Because I was watching the show and thinking, ‘If I were him, I would [take] Phil.’ But he was interested in Jon Lovitz. And I remember thinking, ‘What a fool. What a fool.’ Not that Lovitz isn’t funny. I like Lovitz, too. But to stand back there and watch a guy like Phil Hartman and not see how valuable he would be. . . .” Randy Bennett was also bewildered. “Th e fact that Lovitz got on Saturday Night Live and Phil didn’t was an enormous shock. I love Lovitz, don’t get me wrong, but come on.” Even Lovitz himself was surprised. The very idea of auditioning for SNL struck him as “ridiculous,” he has said. But Michaels — who says Lovitz first came to his attention in the big-screen comedy Last Resort — was obviously impressed by what he saw. So were Al Franken and Tom Davis. As Lovitz later recounted, they came to the Groundlings in search of “a Tom Hanks–looking leading person.” Franken even told Lovitz outright, “You were everything we weren’t looking for in one person, but you were funny.”

Robert Smigel, who began writing for SNL in 1985, recalls that when Michaels returned that year as executive producer after a five-year hiatus (in the process taking back control from executive producer Dick Ebersol, who had been charged with fixing the fractured show after a lame 1980–81 season), he was “looking for people who were outside the box. A guy who’s going to pick Robert Downey and Randy Quaid and Anthony Michael Hall,” Smigel says of the ’85–’86 season’s individually talented but creatively dysfunctional cast members, “is not really looking for Phil Hartman in that particular year. And he was taking a risk. I think maybe Lorne wanted to challenge himself.”

Michaels, though, says Phil could have joined SNL if he wanted to. But he opted out. “He wasn’t passed over. It was his decision.” Not only was Phil still embroiled in his divorce from Lisa at the time, Michaels recalls, he simply didn’t want to leave his comfortable life in L.A. for the bustle of New York.

As per Michaels’s edict (after a thorough housecleaning and the threat of cancellation), starting the following season (1985–86) there would be more emphasis on ensemble work, and no actor would earn more than another. He also planned to revive the “live” component that he believed had diminished under Ebersol by way of more prerecorded material. “It became a television show,” Michaels has said of SNL during his extended absence. “There’s nothing wrong with it being a television show, but I think it was something more.”

Back in Pee-wee land, Phil and his original Roxy cohorts — namely, Lynne Stewart, John Paragon, and John Moody — were relegated to minor on-camera roles in Big Adventure (Phil played a reporter, Paragon a movie lot actor, Stewart a Mother Superior, and Moody a bus clerk). But Phil’s part in the movie’s creation and subsequent box office success (it grossed $4.5 million on opening weekend— enough to cover the $4 million budget — and has to date earned ten times that amount) cannot be underestimated. True, by mid- August of 1985, when Big Adventure was showing on nearly 900 screens across America, Pee-wee’s profile had risen considerably. And, true, budding director Tim Burton (then little-known but mega-talented) and composer Danny Elfman (ditto) imparted their respective magic touches. But according to Varhol, Big Adventure “couldn’t have happened without [Phil] for a number of reasons.” His writing was chief among them.

As Phil told radio broadcaster Howard Stern in 1992, “I wrote a lot of the scenes.” Of course, since Big Adventure was a team effort, it’s nearly impossible to pinpoint which ones are Phil’s alone. But Varhol remembers at least a few portions that bear his co-scribe’s distinctive stamp. Besides the inspired description of Pee- wee’s tricked- out bike, Varhol says some of Phil’s other contributions include snappy action synopses (e.g., “Pee-wee stands pie-eyed and slack-jawed”) and part of Pee-wee’s now-famous “rebel” monologue through which he coolly informs his love interest, “Th ere’s a lotta things about me you don’t know anything about, Dottie. Things you wouldn’t understand. Things you couldn’t understand. Th ings you shouldn’t understand.”

In late October 1985, Phil and Paragon accompanied Reubens to New York, where Pee-wee was slated to host Saturday Night Live on November 3. Reubens and his manager, Richard Abramson, had gotten the OK from Lorne Michaels for Phil and Paragon to serve as additional writers. The arrangement was and remains atypical. In contracts finalized afterwards, Paragon and Phil were each paid $1,750 for their contributions. “Pee-wee was really hot and we hadn’t done the show yet,” Abramson says. “When they said they wanted him to host, I told Lorne that it would be very difficult for other people to write for Pee-wee. It was a specific character; it wasn’t like bringing Justin Timberlake on and you could write a few things and put him in different roles. Pee-wee had a specific voice.”

On their first day at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, in a conference room that lacked enough chairs for all who were present, Michaels introduced Phil, Paragon, and Reubens to SNL’s writers. Being that many of them were Pee-wee Herman fans and the show was Thanksgiving-themed (easy to parody), smiles and laughter abounded. Paragon, for one, felt welcome despite his outsider status. Al Franken and Tom Davis were particularly laid-back and helpful, he says. And Michaels was extremely involved from day one. His TV baby had almost died during his time away, and public opinion was at an all-time low. Critics were especially unkind — one famous headline declared “Saturday Night Dead!” — and ratings reflected the show’s shrinking viewership and diminished status. “Many of the cast members and writers seemed nervous,” Paragon says, “like they had all been threatened before. I was told that Lorne had a way of punishing and rewarding. He would pull a sketch or replace an actor in a sketch, depending on whether or not they pleased him — like Captain Bligh. My experience was that he was totally hands on and a control freak. There was no doubt about whose show it was.”

After seeing Phil in action — he was funny in writing meetings and easy to work with — Michaels expressed his admiration to Abramson. Abramson told him, in effect, “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

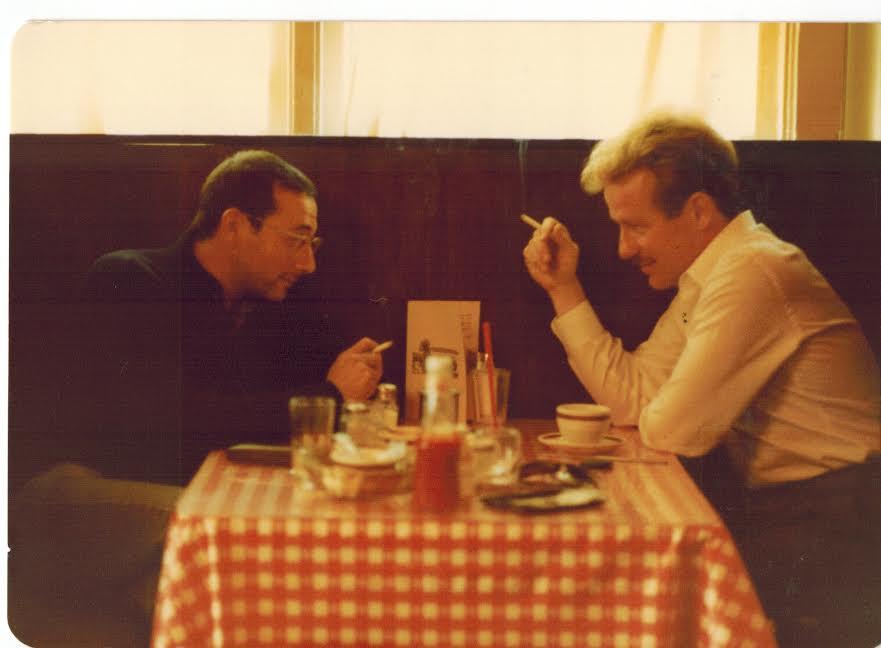

Photo (top, above): Paul Reubens with Phil Hartman, early 1980s. Courtesy of Lisa Strain-Jarvis.