“I reveal all these things about my career, to inspire. I read that 40 percent of Latin kids drop out of high school. And that’s a tragedy in this country. And I know how they feel because I felt the same way. And why is that? That’s just because you don’t feel like you belong in part of the American quilt. Where’s your patch? So I said, if I can show them that I came from this and I made myself and a lot of people helped me. I didn’t do it by myself. And you can’t do it by yourself. But you can hang on in there if you have a dream. And that’s what the show is. It’s to inspire. I did it all over the country, and over to England, and in Latin America. People came up to me after the show and said, ‘I was going to quit dancing. I was going to quit writing. I was going to quit singing. I was going to quit this – but I saw your show, and I thought I could give it a second shot. I could keep trying.’ And I went, ‘Yeah, that’s what the show is about!’ I was going to quit on myself. And I found somehow the strength to keep going.”

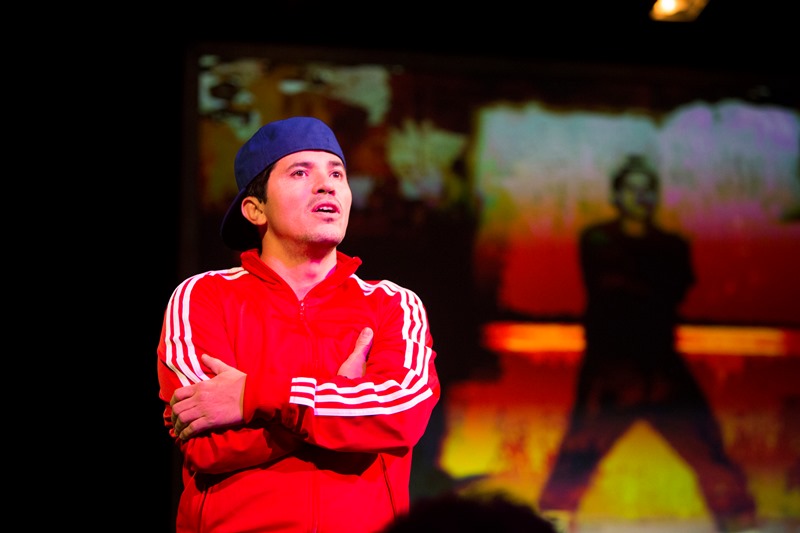

John Leguizamo looks back on his life and career – from Jackson Heights to the heights of Broadway and the big-screen – with his customary rigorous honesty in Ghetto Klown, which he’d staged on Broadway and toured nationally before filming it anew over the winter for HBO. Ghetto Klown debuts Saturday, March 22. In an office in the HBO building, Leguizamo sat with The Comic’s Comic last week – on that day, the news broke that Johnny Legs’ beloved New York Knicks might lure legendary basketball Zen master Phil Jackson out of retirement. But first, we talked comedy.

Ghetto Klown is very meta for you, isn’t it.

“Seeing your whole life flash before you? Seeing your whole life flash before you is, like, when the end of your life, so it’s going to feel kind of weird.”

But you had done this a couple of years ago.

“On Broadway.”

On Broadway. But you did Ghetto Klown on Broadway, did all of the press for that, then went through a process of developing a semi-autobiographical sitcom for TV – how did that inform this version of Ghetto Klown for HBO?

“That didn’t inform the HBO thing. The HBO thing was because. It took me eight years to crack, sort of the career/life/paradigm of the one-man show. Because people had tried before. But somehow it had felt like a laundry list of problems and credits, like a resume. It just didn’t work. So I had to figure it out. It took me eight years, traveling through the country with it, going everywhere with it, and Q&As, Berkeley Rep, La Jolla Playhouse, and then I brought Fisher (Stevens) along with me to help me still keep digging in there. Find out what makes these things, how do you make one work? And to find out what it was, you really have to go in there deep and reveal every fucking thing. Because the audience senses when you’re holding back, or if you’re skipping something. Or if you’re fast-forwarding over something. They know it and they feel it. And all of a sudden, the journey is not as satisfying.”

It didn’t feel different coming back to it after filming the TV pilots? “But TV is a whole different thing. The networks, I don’t know…” he said. “That was a fictionalized version of a fictionalized version.”

He added later: “Making (the pilot) work was hard. Making your life sitcom-able. Because my life isn’t really sitcom-able. So that was rough. It was rough. It was hard. It was not easy. The acting was great. I had great actors. But to really make it. I mean. We were close. It was between us and The Goldbergs. And The Goldbergs beat us out. I was supposed to get on a plane and go to the Upfronts, ‘cause the show was going. Then I get a call at the last-minute, ‘Uh, don’t go. Don’t get on the plane.’”

So that didn’t influence how you approached the work for your HBO taping? “I did have a different approach, but I think that was just a matter of time. I don’t think it was the sitcom stuff. I definitely had distance from it, and things got, it got much more poetic. All the fat got ripped out of it. This is as lean and mean as it could be, and that made it more beautiful. Time is always sort of, fucking, the friend to art.”

At the taping I attended, someone’s phone in the audience started ringing. Mercifully, you won’t hear that on HBO. It didn’t interrupt Leguizamo’s flow, anyhow. “It was during an important moment, too. Where I couldn’t. Dude. I’ve done five of these (HBO specials),” he said. “And I’ve done movies where you’re having breakdowns and some crew member is standing right in front of your eye-line going like this (Leguizamo mimics picking his nose) and you’re like – luckily, I’m a Method actor – so I’ve learned to block everything out except what I’m focusing on. It’s crazy. The Method freed me up so much, because it taught you just to be in the world that you’re creating. You’re a crazy person. Basically, I’m a crazy person.”

In that moment, though, even though it didn’t faze you, did you have a secondary running thought of how you’d need to recapture this scene in one of the other two tapings?

“Yeah, this is shot. Let that shit go. We’ll get it the next time,” he said. “But you’d be amazed. I come from film, too, and I know the magic of what they can do. They can take that ring out. If that’s the best performance, they can take that ring out.”

Wow.

“Technology has gotten to the point now where you can take out so much noise off a track. Before, back in the day, you couldn’t. If there was noise in it, goodbye. See ya. Next take.”

The retrospective of your career in Ghetto Klown includes a chapter on your short-lived sketch comedy series that followed In Living Color on FOX, 1995’s House of Buggin’. But you did stand-up when you were younger, too, correct? “I did a little bit of stand-up,” he said. “It wasn’t my thing. I didn’t enjoy it. They didn’t like me. I didn’t like them. I wasn’t set-up jokes, set-up punchline kind of guy. So I immediately went downtown to the performance art spaces. Luckily they existed when I was in my formative years. So I went down to Gusto House, Dixon Place, PS 122, Knitting Factory, The Garage – I don’t know if, a lot of these places are gone – The Home.”

That was in the early, mid-1980s.

“That was mid- to late ‘80s, yeah. I would go there to perform my stuff, people loved me there. They hated me in the comedy clubs, I hated them. Here is my home! I found my home. All of these drunk college kids, they were my fans,” he said. “All of the emos. All of the punks.”

“I was a storyteller. I wanted to tell stories. I wanted to do characters, and I wanted to do long-form. I didn’t want to do set-up/punchline. It was just not my cup of tea. They let me. I was at The Comic Strip. I was at Dangerfield’s. I was at all of those places for a little while. But I wasn’t happy, and neither were they.”

Do you feel like, there’s guys like you and Christopher Titus who just feel more comfortable presenting stand-up comedy in a more theatrical setting and staging? “Mine is not really stand-up. Mine is a play. It’s written like a play. Long scenes. Lots of characters talking to each other. That’s the hybrid that I pioneered. People talking about yourself on Broadway. Nobody was doing that before. They were doing Mark Twain and young Abe Lincoln. Luckily I was able to see Whoopi Goldberg and see Spalding Gray and Lily Tomlin. I took a little piece of everybody and created my own thing. Which was the biopic; the bioplay of it all.”

“It’s comedy. Still making it funny. I’m still a funny man. I’m still very physical. I can do voices and characters. But I think of it as a play.”

People used to have a real attitude toward guys like you, though, saying, that’s not real comedy. You’re not part of us. “But we had a huge influence on them,” he said. “That’s the thing.”

“Everybody started getting mad physical, after they saw me getting physical, throwing myself on the ground. Doing all the miming. The miming became a huge part of stand-up comedy, and talking about your father, talking about your family. That came from. Where’d that come from, motherfuckers?” he chuckles. “Shit. Pay tribute, when you have to. I paid tribute. I’m not afraid of naming my sources, motherfuckers. Name your sources. Footnote me, bitch!”

The situation now even compared to 10 years ago, there has been a softening of the communities in comedy between clubs, art spaces, and what’s stand-up versus storytelling versus one-person show. You see places in New York City, whether it’s the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, the PIT, the Magnet, Moth, where storytelling or one-person shows are more popular as a way for performers to showcase their acting chops and present themselves to the industry.

“There’s always that group of people doing that, though. Even back in the day,” he said. “There was the historical plays. There was the one-man things about somebody else. People showcasing the shit out of themselves to get an agent. To be famous. Whatever. I was not a part of that bullshit. I was there because I needed to express myself. I come from an invisible people. And I felt like all the people that I grew up with were funny and fucking talented, and my family, there’s some funny, really intelligent people – where are these motherfuckers at? Where are all of these people? All I’ve seen of myself is in the news. And that’s not a place I want to be. So I wrote these things to show people and show myself and other Latin people that we are funny. That we are clever. That we have stories to tell. That we are storytellers. That we always have been. And America just is, has been missing out on us. And showing them what they’re missing out on. It wasn’t about, how do I get to the next step of my career? I’m not about that. Never have been.”

Ghetto Klown looks back on that journey of yours, though.

“I reveal all these things about my career, to inspire. I read that 40 percent of Latin kids drop out of high school. And that’s a tragedy in this country. And I know how they feel because I felt the same way. And why is that? That’s just because you don’t feel like you belong in part of the American quilt. Where’s your patch? So I said, if I can show them that I came from this and I made myself and a lot of people helped me. I didn’t do it by myself. And you can’t do it by yourself. But you can hang on in there if you have a dream. And that’s what the show is. It’s to inspire. I did it all over the country, and over to England, and in Latin America. People came up to me after the show and said, ‘I was going to quit dancing. I was going to quit writing. I was going to quit singing. I was going to quit this – but I saw your show, and I thought I could give it a second shot. I could keep trying.’ And I went, ‘Yeah, that’s what the show is about!’ I was going to quit on myself. And I found somehow the strength to keep going.”

The technology now has made it so much easier and more accessible now for a teenager to find his or her own voice and showcase it. You don’t have to break into the subway conductor’s booth and take over the P.A. system anymore.

“You got this cell phone and you can record the hell out of yourself with it,” he said.

You can make Vines, do Instagram.

“You can make your own porn,” he joked.

I know you’re on Twitter. Do you keep up with everything else online?

“I’m aware of it. It’s a lot to keep up with,” he said. “I try to do Instagram every once in a blue moon. Because I really do like communication through photo, through one photo. And I like Twitter the most. I think it’s a powerful medium. I think you can really communicate a lot of great ideas in 140 characters. The Arab Spring was started through there. It’s very powerful, social media.”

If you were starting out now, would you have embraced technology over the clubs and performing arts spaces, and acting school?

“I definitely still would have done the acting school,” he said. “You can’t bypass the acting school. You can’t just skip that part of your life. If you’re going to be a great actor. Brando, I mean, studied, with the greatest. Pacino studied with the greatest. DeNiro, Benicio Del Toro. Anybody who’s a great actor studied with great fucking people, and went back to the well many times. Sam Rockwell still studies. You can’t skip that. If you want to be a great actor, you’ve got to train like any great athlete. And you better have a great coach. There’s a lot of actors who didn’t go to school. But I guarantee that their acting is not so hot. You might be famous, but I can’t really put any money in your acting. Yeah. I said that.”

So you can’t just be a YouTube star, then?

“You might have a gimmick. That’s fine. That’s great. But that’s only for the moment. See ya!” he said.

So your advice to a young up-and-coming comic then…

“Train! Train like a motherfucker. Perform everywhere,” he said. “But it depends upon what your goals are. I mean, if you want to be a real actor, then you better go to acting class. A lot of comedians can’t act. And a lot of actors can’t be funny. That’s true, too. A lot of dramatic actors cannot be funny. It doesn’t really go back and forth. It’s rare the actor that can do both.”

Here’s a clip from Ghetto Klown in which Leguizamo recalls getting into it with Patrick Swayze during filming of To Wong Foo…

John Leguizamo, “Ghetto Klown,” debuts Saturday, March 22, 2014, on HBO.